Cyber-Attack Vectors in the Automotive Sector – Part 1: Signal Attacks

The push towards ever more sophisticated levels of autonomy in the automotive sector will gradually take our hands off the wheel. But it may also take our mind off the job, and in that lies the potential for significant cyber-attack.

We’re probably a generation away from the fully autonomous robo-taxis of science fiction lore, but increased levels of autonomy are real today. Combined with increasing levels of smart infrastructure and smart roads that can inform the car’s systems not only where they are (in case of satellite loss), but what attractions, activities, charging or refuelling points are nearby, the increase in functionality of automotive systems means we’re not as far as we might think from virtual robo-taxis.

All of which would be just fine – bring on the flying cars and the Blade Runners – were it not for one thing: the Law of the Nefarious Arms Race.

The Law of the Nefarious Arms Race

The Law of the Nefarious Arms Race is that whenever someone builds a system for the general betterment of humankind, no nefarious actor is allowed to sleep until there are multiple ways of turning it into something dangerous, costly, or both. Email and cyber-attack. The internet and data breaches. Movies and piracy – you get the idea.

The car has been, up to now, legendarily difficult to turn into a bad thing. Let’s assume for the sake of this claim that man-made climate change is altogether more complex and can’t be laid entirely at the door of the automobile. Most of a car’s systems have historically been gloriously unsubtle and practically steampunk in their levels of mechanical engineering – rather than computer engineering.

The Mechanical Principle

For mechanical engineering to go wrong, you have to look at either mechanical part failure, user error (did you forget to put gas in the tank?), or some other natural phenomenon.

For mechanical engineering to go wrong on cue, you need to be looking at the stuff of movies – suspicious actors loosening lug nuts, unseen by our hero at the gas station, for instance. That’s what we mean when we say that until now, cars (and also freight trucks, bullion wagons, logistics delivery trucks, and anything that works on the same fundamental principles) have been legendarily difficult to turn into bad things.

Until now.

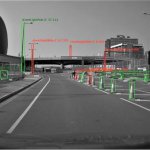

Now though, we’re moving further and further away from the vehicle as a mechanical moving tool, driven by the awareness of the driver, and closer and closer towards the vehicle as a self-regulating, self-navigating, not-quite-yet-self-driving element within an infrastructure of computer data. And while the benefits of doing that are enormous, they also come with two big issues in terms of vulnerability to cyber-attack.

Signals and data.

The Growing Vectors of Signals and Data

Signals and data are weaknesses we’ve intentionally introduced into vehicles in the last 20 years, and certainly as far as data is concerned, the load will only increase as we get more automated automobiles. We’ve added these weaknesses in because the benefits have so far massively outweighed the risks. And the likelihood is that while signal attack vectors are likely to narrow over the next 20 years, making it harder for attackers and safer for drivers, the problem of data interchange density and security weakness may well make vehicles – particularly individual vehicles carrying particular people – the next version of the email hack.

We’ll deal with the attack vector via signals here, and take a look at the data danger of the next generation of vehicles in Part 2.

The Problem With Signals

When we say signals, we mean satellite navigation signals. An absolute gift from the heavens for the geographically inept, the ubiquity of GPS and its sympathetic systems (including GLONASS, the Russian equivalent, and Galileo, the EU version) has also introduced a way into the vehicle that hadn’t previously existed. That means it opens the pathway to a double threat – jamming and spoofing.

Jamming

Jamming is a term everyone in the tech industry will understand. It’s the signal-based version of hacking – hostile actors can interfere with the correct functioning of a computer system for their own benefit.

Jamming a vehicle is easy for those who know what they’re doing. It’s rarely precise, and usually you can’t localize the damage to a single vehicle, but all you need to jam a vehicle right now is a powerful enough satellite signal jammer (available for sale on the internet – your legality may vary). Switch it on at any point, and watch the chaos and confusion unfold in ripples around you, as the satellite signal that tells your GPS where you are, where you’ve been, and where you’re going is blocked, meaning that, in the absence of driver knowledge, or more likely in the presence of learned driver over-reliance on technology, you might as well be in the Gobi desert. And yes, it’s likely to work on police vehicles, too.

So far, so chaotic – what is the point of doing something like that? Well, the idea that you have to take your jammer out for a drive is a little simplistic. Imagine having a handful of powerful jammers in static positions in Times Square, or Downtown Los Angeles. You could create traffic carnage, endanger life, and demand a ransom, as the police searched for not one, not two, but a handful of overlapping jamming signals. With the right timing on your jammers, you could convince a lot of drivers that they have right of way, and effectively watch them drive righteously into one another until you were paid.

Certainly, it’s a lot of work to go to compared to the multi-million dollar computer system hacks that are now being targeted at the essential data assets of companies, but it’s a way of attacking vehicles and the people inside them from outside the immediate area.

Spoofing

But sure, jamming is messy, chaotic, and difficult to monetize. For the real signal-based terror threat of the 21st century, you need to get involved in spoofing.

Spoofing is almost exactly what it says it is. When you switch on a jammer, you lose satellite signal and are effectively location-blind. And so is everyone else. But a spoofer does something much more insidious and personal. Yes, it knocks out your vehicle’s ability to receive satellite signals – but it also replaces the signals you should be getting with a credible alternative, determined by whoever is controlling the spoofer. By replacing those signals at strategic moments, a spoofer can make a satnav direct you straight to where the spoofer wants you, rather than where the GPS says you are.

Yes, it depends on a growing reliance on GPS technology rather than situational awareness on the part of the driver, but the bad news is that a majority of drivers rely on their GPS in exactly the right way to make them spoofing-targets.

And if you’re wondering why anyone would bother to spoof a vehicle, it’s simple – it means the spoofer can put a driver exactly where they need them to be. Potentially, they can then be robbed, beaten, or even murdered for profit.

Signal Attack Mitigations

There is good news on signal attack mitigations, though.

On the one hand, jamming attacks are, as we mentioned, entirely lacking in subtlety. They’re still dangerous, inasmuch as your vehicle goes situation-blind in a matter of seconds. But if the Law of the Nefarious Arms Race holds true, the race element does too – there is now a thriving market in anti-jammer technology. You have to a) know the threat is out there, and b) be able to afford the technology on the ‘just in case’ principle, as most domestic vehicles come without it to keep the sticker price down, but it is out there.

And of course, for logistics fleets, having the backup of a fleet manager means issues can be quickly reported and correct navigational information fed to drivers, to keep them trucking until they’re out of the range of the jammer.

As technology and integrated smart roads become more and more a feature, this will also help defeat jammers, as absolute position data will become accessible by passing points on the road, in case of any interruption of satellite signals.

While spoofing mitigation is not quite that advanced yet, work is underway in scientific circles to develop anti-spoof technology too – and likewise, when smart roads and smart infrastructure are widespread, vehicles will be more resilient to spoofing, thanks to the availability of absolute positioning in the infrastructure, providing an alternative to the falsified position data coming from the spoofer.

So, while cyber-attack on the signals that get you increasingly from A-B in your vehicle are a possibility today, they’re less likely to be a ubiquitous issue as time goes on. Cyber-attacks on data though may be something the tech industry – and civilians – need to look out for more and more. We’ll take you through those threats in Part 2.