Internet access is crucial to human rights

Do we have internet access rights? Should we? In fact, is access to the internet a human right in the 21st century?

Dystopian as it may once have seemed, we are reliant on the internet. Can you remember the last time you went a day without stopping to Google something, or streaming a song, or checking directions, or ordering food online?

In January 2011, the Mubarak regime in Egypt shut down the internet because social media platforms Facebook and Twitter were being used to organize demonstrations against the authoritarian government. The shutdown lasted for five days, but it was too late: the link between on- and offline action had been forged.

The UN made a statement that said that “kill switches” can never be justified under international rights law, even in times of conflict. Hilary Clinton said that people are entitled to five human rights — the four famously articulated by President Roosevelt, and one more: freedom to connect.

Back then, the issue was government regulation of the internet. Over time, the question of internet access has become an issue of lack of government control. Broadband companies are competing with each other, allowing the market to dictate internet costs. Often, the cheapest packages are also the slowest.

The argument that internet access should be a given right reached a fever pitch when the world moved online during the coronavirus pandemic. A study by Dr Merten Reglitz, lecturer in Global Economics at the University of Birmingham found that “the internet has unique and fundamental value to the realization of many of our socio-economic human rights,” and as such must become a human right or else global inequality will worsen.

It’s true: access to the internet is no longer a frivolous luxury. We rely on it for education, healthcare, work and housing. This means that, especially in developing countries, internet access can be the difference between receiving an education, staying healthy, finding a job — or not.

Dr Reglitz’s findings show that even with offline options available, people are still at a disadvantage without internet access. “The internet’s structure enables a mutual exchange of information that has the potential to contribute to the progress of humankind as a whole – potential that should be protected and deployed by declaring access to the Internet a human right.”

The study outlines several areas in developed countries where internet access is essential to exercising socio-economic human rights:

- Education – students in households without internet access are disadvantaged in getting a good education because essential learning aids and study materials are put online. Even pre-pandemic, homework resources were going digital.

- Health – providing in-person healthcare to remote communities is hard, especially in the US and Canada, where people living in rural areas have to travel miles to get medical help. Online healthcare, though not a solve-all, plugs the gap.

- Housing – in developed countries, significant parts of the rental housing market have moved online. Property listings in bricks-and-mortar realtor’s office are still there, but in the fast-paced rental market of the modern day, a webpage refreshes much more quickly than printed listings.

- Social security – accessing public services today tends to be unreasonably difficult without internet access. The option to call service providers is usually provided, with the unspoken caveat of a ridiculously long wait time to the tune of muzak, and such calls not in all cases being free for those who need to make them.

- Work – jobs are increasingly advertised in real time online and people need to be able to access relevant websites to make use of their right to work. Like the housing market, analog just doesn’t cut it if you want to be ahead of the game.

Reglitz’s research also highlights similar problems for people without internet access in developing countries. For example, 20% of children aged 6 to 11 are out of school in sub-Saharan Africa. They face long walks to school where class sizes are very large in crumbling, unsanitary school buildings with too few teachers.

Online educational tools make a significant difference to this picture, allowing children who live far from school to complete their education. More students can be taught more effectively if teaching materials are available digitally and pupils don’t need to share books.

Internet access rights: not just for rich children

It might sound extreme, but internet access in developing countries can be the difference between adequate healthcare and none at all. In Kenya, a smartphone-based Portable Eye Examination Kit called Peek has been used to test eyesight and identify people who need treatment.

There’s a lack of brick-and-mortar banks in developing countries, too, which means that internet access can be crucial to financial inclusion. Further, the impact of crowdfunding for small businesses has long been apparent — the World Bank expects such sums raised in Africa to rise from $32 million in 2015 to $2.5 billion in 2025.

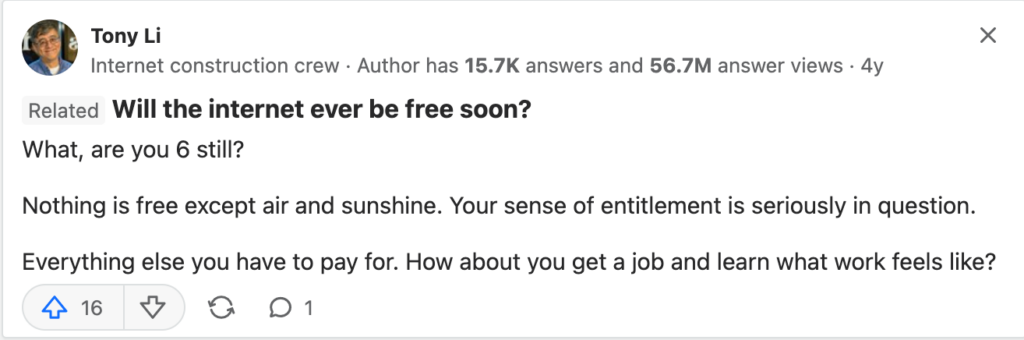

In spiteof all of which, there remains some cultural resistance to the idea that the internet is a human right, though in the most part, that resistance is from generations who pre-date either the ubiquitiy of the internet, or its current level of underpinning of absolutley everything in our society. Exhibit A…

An irate internet user insists that we must sing for our suppers. Struggle on! Suffer!

In answer to the question “will the internet ever be free soon?” We say hopefully — it should be. If something is crucial to obtaining our human rights, does it not become a right in itself?