Global politics to be dominated by semiconductor supply chain, says Intel boss

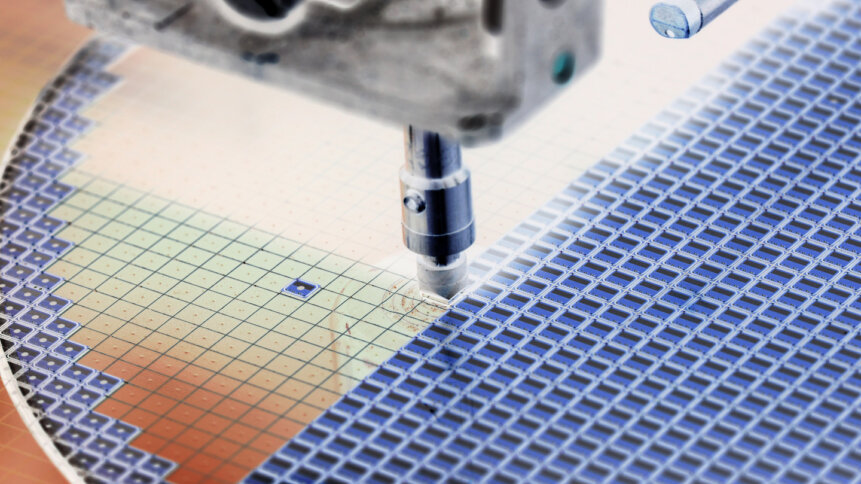

The technology world has seen the impact of the global semiconductor supply chain over the last few years, and in particular, its delicate but definite connection to the movements of geopolitics.

The protectionist, sinophobic stance of both the Trump and Biden administrations in the US, and their use of both rewards for companies bringing or keeping high-level chip development out of China’s hands, like funding through The CHIPS Act, and penalties for companies that still send chips to China for domestic Chinese use, has begun to move the dial, with economic superpowers like Apple and Dell beginning to bring all their chips in-house, and bring them within the US where possible.

The Taiwan factor.

Similarly, the tension between Taiwan (the world’s leading home of semiconductor production) and its neighbor, China, has long been a geopolitical reality. It couldn’t be anything less, since Taiwan declares its own sovereign state, and China believes Taiwan is a part of Chinese territory. As the US puts economic pressure on China in an attempt to reinvigorate its own domestic semiconductor industry, the tensions between China and Taiwan are only likely to intensify. And those tensions become global when we remember that President Biden has said he will send troops to protect Taiwan’s independence in the event that China invades the country – something he didn’t do in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which shows the importance to the US of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry.

Add to that the potential diversification of the semiconductor supply chain, with players like TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company) looking seriously at diversifying their supply chains in countries like Germany and Japan – as well as affirming their US connections, and semiconductor supply chains becomes a febrile mover of global geopolitics.

That’s a fact that’s been recognized by Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger at the World Economic Forum in Davos.

Oil RIP.

Drawing a parallel with the longstanding global norm of oil resources determining global economic power, Gelsinger said that the geolocation of semiconductor supply chains would be critical to geopolitics in the future. “The location of oil reserves has defined geopolitics for the last five decades,” he said, then added “Where the technology supply chains are, and where semiconductors are built, is more important for the next five decades.”

His comments came in the context of Intel’s commitment to creating semiconductor plants in Europe, the US, and elsewhere. That kind of action, he said, if replicated across the industry, would result in a “balanced, resilient supply chain,” and the “globalization of the most critical resource to the future of the world.”

The logic of semiconductor supremacy.

In several senses, his words make a stark sense. The world is rushing to free itself of the dependency on planet-burning fossil fuels like oil for its transportation and power needs, with the rise and rise of electric vehicles and grids, and alternative power sources for a mainstream grid. That’s a move that has received significant impetus in the last year by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its strangling of Europe by controlling gas pipelines – a move that in itself has significantly impacted the economic stability of a continent, and which has had ripples reaching across to the US too.

Meanwhile, the world continues to grow more and more dependent on computer and cloud technology, and the semiconductors that empower them. The resources of oil and semiconductors are travelling in different directions in terms of their destiny, so the time feels right to acknowledge the shift in global geopolitics that will follow the replacement of oil in terms of the fundamental driver of economic prosperity.

The Intel investments.

Intel has already committed to a $20 billion investment in two new US semiconductor facilities, and anything up to $90 billion in new European semiconductor plants.

That commitment came specifically in response to the tensions over China, Taiwan, and the US, though the announcement of potential CHIPS Act finance as a carrot to entice chipmakers to commit to newbuilds in the US was a significant persuader, too (The CHIPS Act will potentially deploy $200 billion of incentive funding as part of its attempt to reinvigorate the US semiconductor industry).

Gelsinger acknowledged that his assessment of the future pre-eminence of semiconductor supply chains was also mirrored in the fortunes of Intel itself. “If we’ve learned one thing from the Covid crisis and this multi-year journey that we’ve been on, it’s we need resilience in our supply chains,” he said, explaining that the company’s recent massive investments in semiconductor plants were aimed at “levelling that playing field so that good investment decisions can be made.” That means they’re an investment in Intel’s aim to re-establish itself as the leading Western semiconductor manufacture after a destabilizing few years.

But for all the self-interest behind the Intel CEO’s pronouncements at Davos, there’s a distinct economic logic behind them, too. The age of the semiconductor supply chain, not just as a social mobilizer, but as a leading fundamental lever of geopolitical power, could be with us within the next decade. The faster the development of green alternatives to fossil fuels is, the sooner that age will become an indisputable truth.