Why does no one want a used electric vehicle?

- Used EVs are piling up in scrapyards as a lack of resales has a knock-on effect on new vehicle sales.

- New is deemed inherently better than old in a rapidly evolving technological era.

- Electric cars do more than just drive – one might save you in an emergency!

In south-east Queensland, storms and flash flooding on Christmas day caused power outages. If extreme weather caused by climate change wasn’t enough of a motivator to switch to more climate-friendly electric vehicles, maybe their potential to save you in the event of a climate disaster is.

Without power, residents of south-east Queensland couldn’t get through electric gates, septic tanks began to fill, air conditioners didn’t run and in the heatwave that followed the storm, refrigerated food went bad.

Owners of electric vehicles equipped with “vehicle to load” systems, the backup power system that allows the cars to act as emergency generators, stepped in to help out. One of those owners, Kristy Holmes, used her BYD electric car to power her 11-year-old son’s dialysis machine.

Holmes said she had known she could “use my car for good things” since she made slow-cooked mulled wine for a movie night using the car’s electric system.

As you do…

“It’s the most amazing car I’ve ever owned. Now it’s been able to save my son during a storm, I don’t think I’ll ever go back to a petrol (gas-powered) car again.”

Everybody loves a feelgood story, and these tales of EVs to the rescue will certainly warm the cockles of the industry’s heart. Sadly, it needs all the good news it can get, because it’s running into a new and serious hurdle: it turns out drivers don’t want used EVs.

The draining battery of used EV values

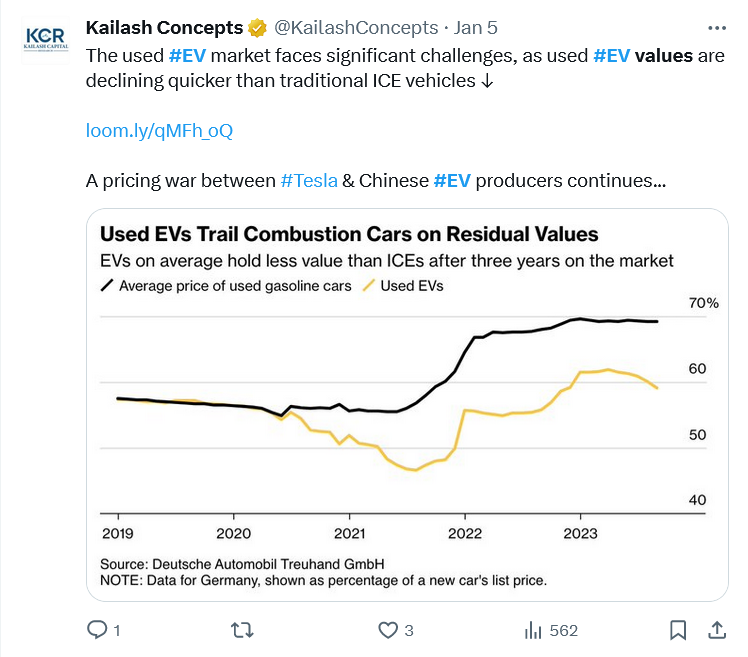

In the $1.2 trillion second-hand market, prices for EVs are falling faster than those of vehicles running on planet-burning fossil fuels.

We can look to China for a cautionary tale: lucrative subsidies turned the country into an EV giant, but the lack of second-hand sales produced “weed-infested graveyards” of abandoned vehicles. That’s had a knock-on effect on new EVs, too, and the worry is that if similar graveyards crop up in the US and Europe, it’ll strengthen calls from conservative politicians to roll back aid for the industry.

One of those weedy graveyards in China… Image via Bloomsberg.

Warning signs appeared early in 2023, when Tesla started aggressively cutting prices in an effort to prop up sales. That spurred a price war as other manufacturers followed suit, and profitability dropped for some, while others saw already steep losses increase.

Because most new vehicles in Europe are sold via leases, the automakers and dealers who finance the transactions are trying to recover losses from plummeting valuations by raising borrowing costs.

Some of the biggest buyers of new cars, including rental firms, are cutting back on EV adoption because they’re losing money on resales, with Sixt dropping Tesla models from its fleet.

“When a car loses 1% of its worth, I make 1% less profit,” said Christian Dahlheim, who heads VW’s financial services arm. The issues with used EVs, he said, have the potential to destroy billions of euros in earnings for the broader industry.

“There isn’t used-car demand for EVs,” said Matt Harrison, Toyota’s chief operating officer in Europe. “That’s really hurting the cost-of-ownership story.”

Value issues with used EVs.

Mobility offerings and ride-sharing startups took up much of the sales of EVs, but their demand is limited. As the technology used in EVs is continuing to evolve, few want the older model because new is markedly better. Also, the usual boundaries apply to second-hand EVs: things like poor charging infrastructure mean people – even those worried about their emissions – don’t want to switch to electric.

Prices for used EVs slumped by around a third in 2023, compared to a decline of just 5% in the overall used market. Even after significant price cuts, EVs take longer to sell than their gasoline competitors.

“One has to slash prices significantly just to get customers to look at EVs,” said Dirk Weddigen von Knapp, who heads a group representing VW and Audi dealers.

The growth of graveyards

In Germany, Europe’s biggest auto market, most new vehicles are first sold as company or fleet cars and then re-enter the private second-hand market one to three years later. But with orders slowing even for new EVs, more and more used models are sitting on lots longer than 90 days, meaning they’ve become “risk inventory,” according to the Deutsche Automobil Treuhand market research company.

Another issue is the fact that this is the first time the industry has had to handle used EVs. While it’s easy to price a second-hand combustion-engine car by looking at its age and mileage, there isn’t yet a widespread use of tests to determine the quality of an EV’s battery.

Some EVs are still performing well years after their introduction, with less-than-expected battery degradation, said Mike Tyndall, an analyst at HSBC. Teslas can sell quickly in the second-hand market because of the brand’s reputation as a technology leader and its regular wireless software updates.

There’s also a cult following of the i3 electric car BMW introduced a decade ago that keeps them selling on the second-hand market.

A happy i3 owner via CAR magazine.

Ayvens, a fleet management company handling around 3.5 million vehicles, said the uncertainty around EV technology will convince more customers to lease rather than buy — accelerating a shift away from owning a car to driving it for a fee.

“EVs are a booster of the transition of ownership to usership,” said Annie Pin, Ayvens’ chief commercial officer.

What that means for profits is one thing, but the environmental implications of single-use cars, electric or not, means that should be a cause for concern.

The graveyards seem set to grow.