How environmentally friendly are Iceland’s data centers? – Part 1

• Data centers face a pressing need to reduce their climate impact.

• Iceland’s data centers offer attractive power and processing rates.

• But with rising AI data demands, the sustainable answer is not obvious.

Part 1: Demanding conditions

“Data centers are here to stay,” Iceland’s president Guðni Thorlacius Jóhannesson said when introducing the annual Datacenter Forum in Reykjavik last month.

“Last night, I attended a sporting event, and I took loads of videos. On the way back, I listened to music, Spotify, and did a tiny bit of work after that. Downloaded stuff, necessary stuff, unnecessary stuff, and didn’t pay any attention to the energy all this takes, because it’s just somewhere in a cloud. I don’t see black smoke billowing… I just don’t see the energy that is used.

“This might be a cause for concern, or at least it should make us aware that if we want to be sustainable, we have to be conscious of the energy we use. It is our duty to make sure that we are conscious and to seek the best ways to go forward.”

Iceland certainly sees itself as one of the most viable options for handling our ever-growing data demands, and with good reason. The country has a mild climate all year round, with temperatures ranging from just above freezing in the winter to around 54°F (12°C) in the summer, and the range is even smaller on the south of the island.

This essentially provides data centers, that produce a lot of heat but must be kept at around 68 to 77°F (20 to 25°C), with a free, natural cooling system that doesn’t require any energy. Iceland’s data center industry boasts an impressive power usage effectiveness (PUE) range of 1.05 to 1.2, thanks to the lack of air conditioning systems and instances of hardware overheating.

Iceland’s president Guðni Thorlacius Jóhannesson introducing the annual Datacenter Forum in Reykjavik in October. Source: TechHQ

But if energy is needed, Iceland has that covered, too, at least from an environmental perspective. The country runs almost entirely on renewable energy, with 100 percent of its electricity generated from hydroelectric (73 percent) and geothermal (27 percent) power sources. Only about 15 percent of the country’s energy usage comes from fossil fuels, said President Jóhannesson, and where they are used, the primary culprit is the mobility sector – the country is, after all, an extremely popular tourist destination and stopover for flights to other countries. But the non-electricity components of aluminum smelting, the country’s largest industry, are also partially to blame.

The strong sales pitch of Icelandic data centers

Hydroelectric and geothermal sources have low variable costs when operational and are not subject to fuel price fluctuations, so energy companies can offer long-term price stability. That all adds up to a strong sales pitch for businesses looking for a sustainable and cost-effective location for their data.

Even those that are more security conscious than financially or environmentally motivated may be tempted by the island. Iceland is often named one of the world’s safest countries and benefits from a political landscape that’s historically stable. Data centers are also ideal power customers for Iceland, as they consume electricity at a fairly constant rate, so power companies are willing to agree to ten-year power purchase agreements (PPAs) at favorable prices. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has demonstrated how valuable such an agreement can be. But even so, executives from the handful of data center operators with an Icelandic presence are not lifting their foot off the gas pedal when it comes to promotion.

“It takes something to get customers on an international scale to move data to a little rock in the North Atlantic,” said Halldór Már Sæmundsson, the chief commercial officer of Borealis Data Center at the Datacenter Forum. “We need to prove ourselves time and again.”

Hellisheiði geothermal power station in Hengill, Iceland. Source: TechHQ

With the rise of AI in the mainstream over the last year, our data demands have skyrocketed. Mike Allen, the COO at Verne Global data centers, said that an AI “inflection point has come” at the Datacenter Forum. He added: “From the data center perspective, we’ve seen this explosion of use cases have an effect on the infrastructure and the demand for infrastructure.”

“In 2018, there were roughly 24 data centers in the US that were over 10 MW – and 10 MW is a big data center. Now, there are hundreds, literally hundreds of them out there, and this is because of those use cases. They are now available to people with large language models.”

The big three Icelandic data center providers

Iceland has three main data center providers, atNorth, Borealis, and Verne Global, which boast a total of about 200 MW in capacity. These, along with a handful of other smaller facilities, offer typical colocation services, where businesses can rent the infrastructure they need to house their servers, data storage, and networking equipment. Beyond this, the companies can host GPU, CPU, and IPU-intensive applications, catering to the ever-increasing range of industries that require high-performance computing.

Cloud services work well for brand-new businesses who don’t know what their idea is worth yet, so spending hundreds of thousands of dollars on kit could be a waste. They can also work for extremely high-variance businesses with fluctuating loads. But for other types of AI businesses, using data center facilities could be a vastly more cost-effective option.

Smári McCarthy, the founder of environmental data provider Ecosophy, said at the Datacenter Forum: “If we look at the cost of storage, storing one petabyte in the cloud is going to cost you $8,000 to $17,000 a year, depending on where you go, what kinds of availability [they have] and other parameters.

“Whereas if you go into renting bare metal, that goes down by a factor of two to three. And then if you buy your own hardware and stick it in atNorth or Borealis, that’s going to go down even further, to a factor of maybe six.”

But one of the big concerns with Iceland’s data centers is latency – the delay between a user’s action and the system’s response. The country’s geographical location means that the data transfer between the facility and the user can only be so fast, compared to a data center in the same city.

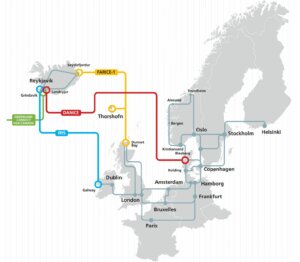

Submarine cable network of Iceland. Source: Farice

However, two things were made clear by Þorvarður Sveinsson, the CEO of submarine cable company Farice. The first was that the cables built between Iceland and the rest of the world allowed for excellent transfer speeds of, for example, 10.5 milliseconds to Dublin and 15 milliseconds to London.

The second is that many applications need computing power but are not latency-dependent. He said: “AI really requires big data analytics… processing needs a lot of power in analyzing data. Maybe we don’t need to do that processing in the city of London, maybe we could do that in a more efficient way in Iceland. We have built a really robust channel for transporting all the data to be processed in the most economical and sustainable way.”

What about latency?

Shearwater, a marine geophysical services company that images subsea environments, proved his point. “We don’t have any complaints from users,” said UK processing and imaging manager Andrew Brunton when explaining how transferring sensor data to the atNorth facility takes 6.6 milliseconds longer than London and ten milliseconds longer than Copenhagen.

The company chose to transition to atNorth when cloud services started looking more expensive than on-premises and consequently reduced its monthly spending from $219,500 to $17,800 (£173,000 to £14,000). It also reduced the carbon dioxide emissions associated with its compute by 92 percent.

Shearwater GeoServices vessels Empress and Amazon Conqueror transfer sensor data to data centers in Iceland. Source: Shearwater

A similar story was shared by Wirth Research, a computational fluid dynamics company that moved its operations to a Verne Global facility in 2021. As only the visualization was happening at the Icelandic data center, and no files were being transferred between there and its headquarters in the UK, the latency did not matter.

Indeed, the company reduced its computational carbon emissions to nearly zero and relocated to a solar-powered, zero-carbon office thanks to relocating its IT infrastructure. The major financial services business BNP Paribas re-engineered the backend of its computational platform to accommodate the lower latency of Iceland’s data centers, as it was a worthy trade-off for cost savings and emissions reduction.

Farice’s Mr Sveinsson said that no private company had offered to buy a strand of its network yet, but that that may not be the case forever. “The impact of AI, the discussion of sustainability, and of green sources of power, is really creating a lot of demand today,” he said.

SubCom’s cable installation vessel, CS Durable, laying the IRIS submarine cable. Source: Farice

Along with data, demand for sustainable options is also rising, which is, at least in part, due to the implementation of new environmental standards like the EU Green Deal or carbon taxes. Many countries are not in a good place with their emissions and are actively seeking ways to reduce their carbon footprint.

As Iceland’s primary energy provider releases just 0.38 g of carbon dioxide per kWh of energy, the nation can pass on those benefits to its data center customers as a unique selling point. IBM, which partners with Borealis for cloud storage, gives its customers the choice of where they want to run their workloads, including the carbon-neutral setting of Iceland.

Farice is participating in large projects that will connect its data centers to new, faraway corners of the world. These include ‘Far North Digital,’ which will connect Iceland to Japan via Ireland with a 14,000 km cable by 2027. There is also the ‘Pisces’ project, which will connect Ireland to Portugal, Spain, and France. Complex projects like this, which cross multiple jurisdictions, are unlikely to have been greenlit if demand for Iceland’s sustainable data centers was not there.

Read ‘Part 2: Energy and cables’ here.

Read ‘Part 3: Data centers’ here.