The end of the Zoom boom?

- More companies require staff in office some of the time.

- Meta staff are due back in the office from September.

- With digital nomads on the rise, real estate is suffering.

Post-pandemic, many bosses share the feeling that remote work was a short-term fix. Working from home was a necessary deviation the norm but employees should be back at their desks ASAP.

Bart Valdez, CEO at Ingenovis Health, a Colorado-based staffing firm with 1,600 corporate employees, said the environment he grew up in required a suit and tie, and to be “at the office at 8AM – no excuses.”

However, he’s listened to his employees and had a change of heart: the younger generations have different lifestyles and pressures, and working from home better meets their needs.

It helps that remote work hasn’t harmed productivity at Ingenovis, where recruiting has improved because the company gets more applicants as a direct result of its approach. One-third of the company’s employees are back in the office, another third are totally remote, and the last group follow a hybrid pattern, a mix of at-home and in-office work.

This represents a trend that has developed post-pandemic. As more corporations call workers back into the office, few employers have required on-site work five days a week from staff. Despite arguing the importance of preserving company culture, most businesses, including the likes of Meta, have called for a partial return.

From September, Meta staff will be required to return to the office three days a week.

Some firms have backtracked in favor of a more flexible system, and others have abandoned back-to-work plans after resistance from employees and other pandemic-based changes. All of this is to say that the overall amount of work done from home has remained steady this year.

According to monthly surveys of thousands of workers by WFH Research, the proportion of work carried out remotely has stayed at about 28%. Another survey by Leger showed that 27% of full-time workers said their employers had become more lenient about remote work over the last year.

Early in the pandemic, Valdez found that managers could make intense use of technology to keep energy up. He didn’t want to lose the culture at the $700-million staffing company, spread across seven units, which he described as “really dynamic, so energetic.”

In order to maintain this, Valdez said there was “a significant amount of forced communication,” that saw some employees working from home on Zoom fairly constantly.

Zooming back to the office

Ahh, Zoom. The backbone of lockdown socialization. In 2020, the company’s shares skyrocketed sixfold as it emerged as the go-to video conferencing service for online meetings. Zoom remains a leader in the post-pandemic remote work trend – but is gradually calling its own staff back into the office.

For the first time since the pandemic began, all employees within a 50-mile radius of a company office are now required to go into the office at least two days a week on a hybrid schedule. As of January 2022, only 2% of Zoom’s employees worked on-site.

According to a Business Insider report, Zoom’s stock stagnated this year as workers across the country returned to the office and the reliance on video communications dropped. This comes after a plummet in the company’s stock towards the end of 2021, since which time it’s lost at least $100 billion in market value.

A spokesperson said “we believe that a structured hybrid approach – meaning employees that live near an office need to be on-site two days a week to interact with their teams – is most effective for Zoom.

“As a company, we are in a better position to use our own technologies, continue to innovate, and support our global customers.”

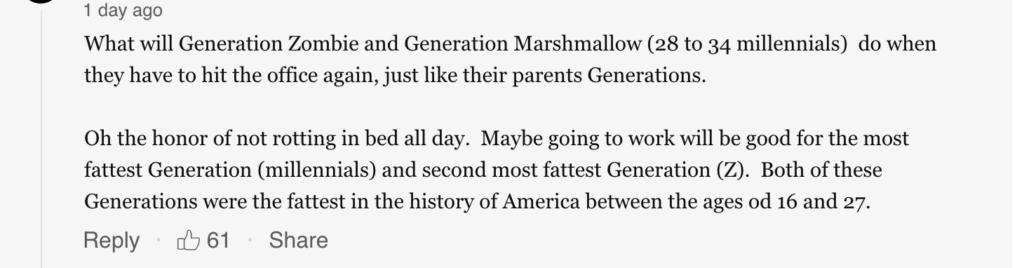

One commenter on the report asked if the back-to-work order from Zoom meant “get back to the office so we can tell other companies that it’s best to work remotely and use zoom [sic]?”

Another argued that “this is all because companies are getting pressured to bring tax revenue back into cities. Has nothing to do with productivity. If you pave roads, you have to physically go to work. If you write code, you don’t.”

YOU MIGHT LIKE

Zoom – the next generation

Remote work enabling a new way of life

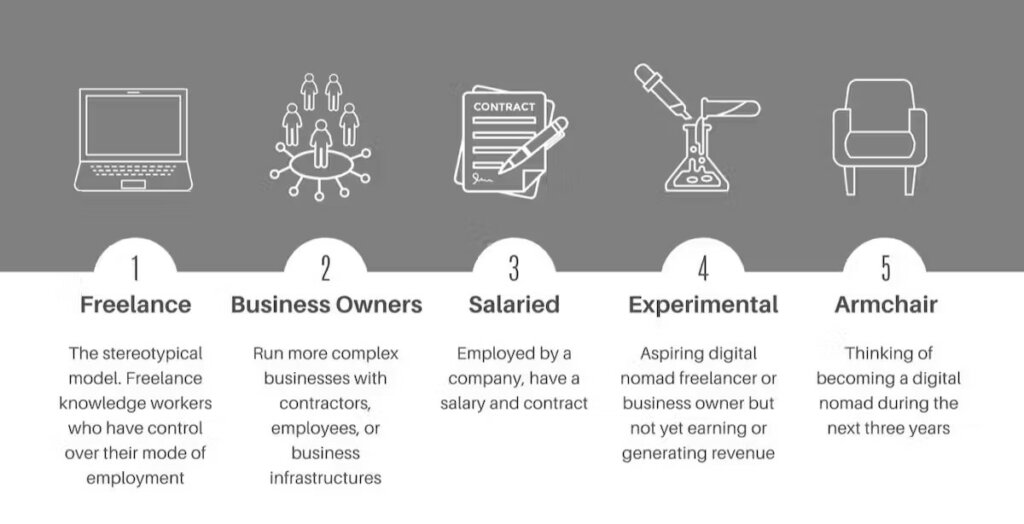

Another trend that has emerged post-pandemic is the concept of the digital nomad. Although they existed before 2020, a generation adapted to online work and itching to explore the world as it emerged from lockdown was ready to embrace a new lifestyle.

Before COVID, the number of people who could be called digital nomads was minimal enough that the impact of the lifestyle couldn’t be definitively tracked. The phenomenon was niche and saw travellers working illegally on tourist visas.

Remote work means scenic locations. Source: Twitter.

Now, the most recent estimate puts the number of digital nomads from the US alone at 16.9 million – that’s an increase of 131% from pre-pandemic 2019.

A recent survey commissioned by SafetyWing of 550 respondents – 250 office workers, 250 remote workers and 50 digital nomads – showed that almost three-quarters of digital nomads chose to go remote as a direct result of the pandemic.

It also found 90% and 86.8% of respondents expressed interest in becoming a remote worker and a digital nomad respectively. The cost of living helps explain this rise, with 78.3% of Americans considering or committing to working remotely citing this issue as a reason.

Theoretically, supporting digital nomad employees widens the pool of talent. Further, they are often highly motivated and productive (Wouldn’t we all be?).

There are issues with compliance that arise, meaning a company that allows remote work from across the world will have to develop policies and procedures that ensure compliance with local and international regulations.

Source: Creative Commons

Several categories of digital nomad have emerged. However, the impact of their travel is reshaping the communities from which they work. Chiang Mai in northern Thailand is often dubbed the digital nomad capital of the world.

Areas of the city are lined with coffee shops, co-working spaces, Airbnbs and short-term lets, all affordable to those on western wages – but out of reach for locals.

There’s some irony at play there. Workers don’t want to return to their offices in the US, for example, due to commute time and cost (they can’t afford to live closer to the office). It makes financial sense to move somewhere cheaper (and, let’s face it, often sunnier and prettier).

Lisbon is in the middle of a housing crisis: with the average salary in Portugal under US$20,000 (£16,226), a one-bedroom apartment in digital nomad hotspots in the capital account for at least 63% of a local wage – one of the highest ratios in Europe.

Of course, back at home, commercial real estate isn’t doing well either: empty office buildings are a money pit for landlords and companies that invested millions in office space in city centers. And the damage extends far beyond the big businesses with downtown office blocks – the community of smaller businesses that exist to serve on-site workers, from coffee shops to restaurants, to gyms and bars and book stores – will all feel the pinch of empty commerical buildings.

If workers don’t return to the office, it could have significant impact on businesses in big cities. With business down, tax revenue declines. Conspiracists say that’s why there’s such a push for staff to work a hybrid pattern, if not come into the office full time.

One response to the New York Post’s report on Zoom’s return to the office. *Contentious opinions and atrocious spelling both the poster’s own.*

Either way, with even Zoom saying goodbye to remote work, the option of taking calls in your PJs after a lazy breakfast-in-bed might soon be a distant memory. The labor market is consumed by the debate, and workers’ rights feel like they’re being debated anew.